The DVA looks almost like a hook, and the cavernous malformation is on the inside of that hook.” Disturbing a large DVA like Vern’s can cause a catastrophic stroke. Vern’s wife Tiffany explains, “The cavernous malformation that keeps bleeding is located too close to his DVA to remove.

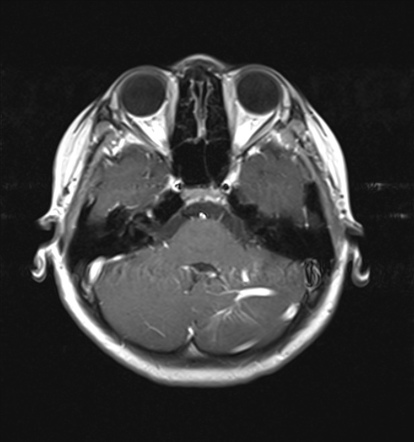

Vern has consulted numerous surgeons about removing the most problematic of his cavernous malformations (also known as cavernoma or cavernous angioma). He also has been recovering from gait and vision deficits. “My reaction time was just not near what it needed to be to operate a vehicle safely.” Vern is driving again, but not on interstates or during times of heavy traffic. As a result, he closed his business as a mobile fleet service mechanic to focus on his recovery and his family. It was not until two years later that Vern had his first hemorrhage. While a DVA by itself typically does not cause symptoms or complications, Vern’s DVA had set the stage for the development of more than one cavernous malformation. Doctors diagnosed him with multiple cavernous malformations surrounding a large developmental venous anomaly (DVA ), a dilated malformed vein, in his brainstem. From the subsequent CT scan, Vern and his wife Tiffany were surprised to learn that Vern had a more serious and long-term condition. In 2004, Vern, then a 28-year-old father of two, hit his head while practicing jujitsu. Patient Story: Vern DVA with Cavernous Malformation This further highlights the importance of obtaining gradient echo or SWI imaging in order to determine whether a DVA is present or associated with multiple lesions. Genetic testing is generally not recommended if there is an associated DVA present since these are more associated with the sporadic form of the disease. The authors recommend that having a DVA should not be an exclusive indication for proceeding with surgical resection of CCM. A 2020 study (Chen et al) found that sporadic lesions with an associated DVA did not increase patient risk of hemorrhage or hemorrhage size during a bleed. In general, surgical resection of a DVA, even during cavernous malformation resection, is not recommended due to the risk of edema, hemorrhage, or infarct. While additional research is needed, specifically in mouse models of the illness, it is possible that both too little and too much blood clotting can have negative consequences for cavernous malformations. Related, researchers have suggested that clotting in a DVA from causes other than COVID may be one cause of cavernous malformation hemorrhage (Zuurbier, 2019). It is hypothesized that a COVID-related blood clot may cause the backup of blood into an associated cavernous malformation lesion. dva and hemorrhage riskįindings from the COVID registries at the University of Chicago and Alliance to Cure Cavernous Malformation indicate the presence of a DVA may make sporadic cavernous malformations more susceptible to hemorrhage during COVID infection (Shkoukani A, 2021). As imaging technology advances to 7T MRI, it is possible that abnormal veins will be discovered in association with most sporadic cavernous malformations.

DVAs are not always visible on MRI, even with 3T MRI. Later, a second mutation in the area of the DVA in any one of four genes – MAP3K3, CCM1, CCM2, or CCM3 –leads to the development of the cavernous malformation. During brain development, a localized genetic mutation in the PIK3CA gene of a vascular cell causes the development of the DVA. Research indicates that, for those with a DVA, the DVA is likely the cause of sporadic cavernous malformation development (Snellings, 2022). They can be found with a solitary cavernous malformation lesion or with a localized cluster of lesions. A DVA is most often associated with the sporadic form of cavernous malformation. With the recent advent of higher resolution imaging techniques, the association between CCM and DVA has become a more common finding. DVA associated with a cavernous malformation

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)